Deconstructing solar

How solar plants in NYS are decommissioned

What will happen to solar facilities in NYS when they reach the end of the road due to age, damage, or owner insolvency? Will they slowly decay where they stand? Will projects be left for future generations to deal with?

The good news: most NYS utility-scale solar projects have decommissioning plans, and many have funding in place for cleanup. The bad news: decommissioning plans and funds are not a state requirement for all solar installations, and there’s no guarantee that decommissioning funds allotted are sufficient or will be available when needed.

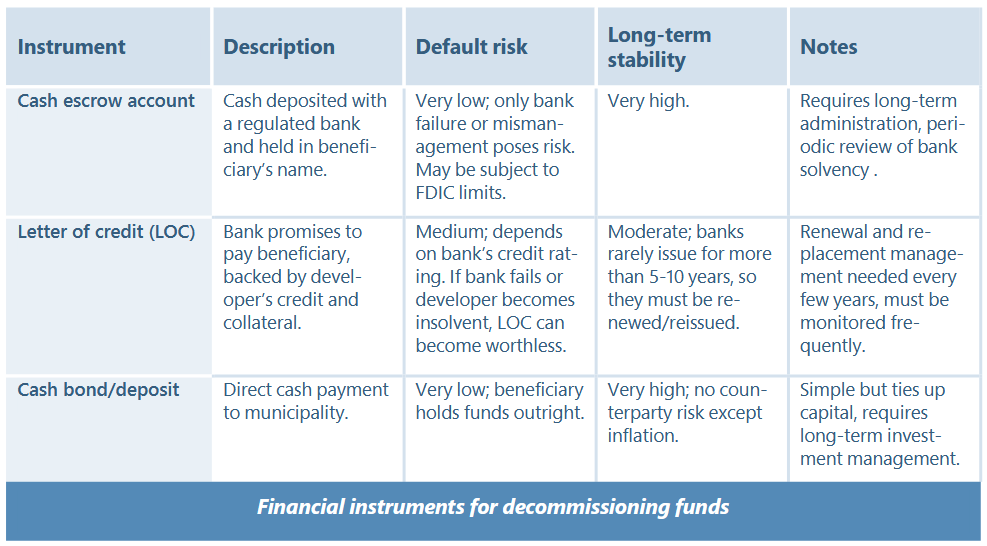

Not all forms of financial security are created equal. A letter of credit is not the same as cash escrow or cash bond. Municipalities need to know money is readily available when a project needs to be decommissioned. Plans for three 100-MW solar plants put decommissioning costs (with contingency funding) at $4.4 to $5.6 million, according to developer estimates.1

Solar deconstruction

As far as I can determine, no utility-scale plant in NYS has been formally decommissioned as of this writing.2 This is important to keep in mind, because some issues are only likely to come to light when projects start to be decommissioned in another 20-25 years.

In my post Repowering solar projects, I discussed what happens at the end of a solar project’s engineering life. Often, the project is repowered: outfitted with new racking and panels, new inverters, and so on. It is then put back into service for another 25-30 years.

If the project has reached the end of its engineering lifespan and hasn’t been very successful, or the developer has other reasons for not repowering it, the project may be decommissioned. Decommissioning involves removing the racking, panels, wiring, inverters, fencing, utility poles, roads, and anything else that wasn’t part of the original landscape.

Certain items can be salvaged and recycled, such as steel racking. Many parts of panels are potentially recyclable as well, but currently recycling is too expensive for most developers to consider. It typically costs $25-$200 to recycle a panel, versus $2-$5 to dispose of one in a landfill. My post Solar panels and recycling in NYS discusses these options in more detail.

The jury is still out on exactly how we will dispose of solar panels. Will they be treated as hazardous waste? Will some panels be classified as hazardous, but not others? This designation has a significant effect on disposal and transportation costs. Recently, the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) offered some limited advice on whether solar panels should be classified as hazardous waste. They found that even within a manufacturer and model, some modules tested as hazardous while others did not.

Not everything is removed from the site. Certain components are usually left in place after decommissioning, including anything (wires and portions of footings, for example) direct-buried 4’ or deeper in agricultural soils or 3’ or deeper in non-agricultural soils. While these may not interfere with some farming operations, they would interfere with installing drainage tile; in upstate NY, the frost line is typically 3’-4’ deep, and tile is often installed below that depth. Buried components may also create problems with later development on the site, as the location of those components may not be well documented and could create surprises during future excavation.

What’s in a decommissioning plan

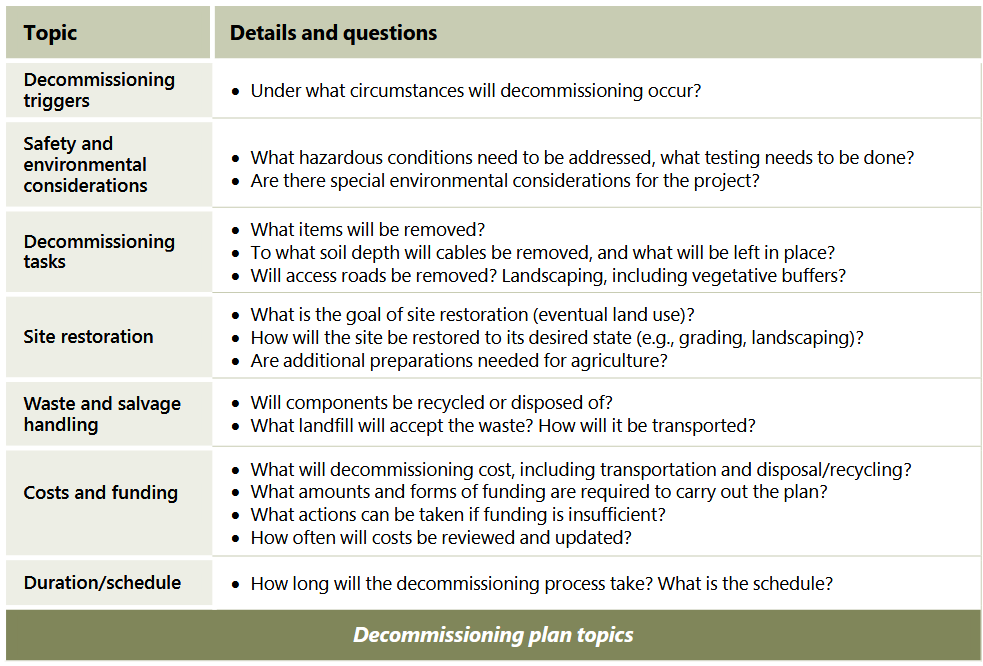

To ensure that the project site is restored to an acceptable state, all solar installations—from residential arrays to grid-scale plants—need decommissioning plans. In NYS, decommissioning plans for small projects (under 25 MW) are often required and reviewed by the municipality where the site is located. Not all municipalities require them, though. For projects over 25 MW, the Office of Renewable Energy Siting (ORES) requires a decommissioning plan to be filed and funded. Plans need to address topics such as these (not necessarily in this order):

Decommissioning triggers

Decommissioning usually occurs when the project either

Reaches the end of its engineering or useful life, typically after 25-30 years or more

Hasn’t generated any electricity within a specified period (12-18 months)

Sustains major, widespread damage—for example, from a weather disaster

Note that decommissioning is generally a last resort. Even weather damage is more likely to result in repowering, if insurance coverage was adequate.

Safety and environmental considerations

Because solar arrays may be placed on sensitive locations such as wetlands, some care may be needed in removing components. The same is true for agricultural soils that are especially prone to compaction. The presence of such conditions and suggested precautions should be included in the decommissioning plan. Sites located in special habitats (e.g., winter raptor habitat) may have restrictions on when decommissioning activities can take place.

Soil and water testing should be done 1) before construction, 2) periodically during project operation, and 3) upon decommissioning. Initial testing is needed to rule out any possibility the site was previously contaminated.

As I mentioned, because we have so little hands-on experience with decommissioning, we don’t know what to expect in terms of possible environmental contamination from solar panels, especially from broken and damaged ones that have been left on-site for any extended period. I’ve touched on the possibility of contamination on solar sites in other posts and will revisit it soon. Testing should be done early in the decommissioning process to determine whether PFAS or metalloid substances exceed acceptable levels. Any contamination will require prompt remediation.

Environmental cleanup costs for solar projects could potentially be considerable. Such costs are not usually included in decommissioning funds, but municipalities would be wise to prepare for the possibility that remediation may be required. While the developer may ultimately be liable for these costs, projects tend to change hands regularly, and insolvency does occur. The state should also be actively engaged in monitoring sites and, if necessary, exploring potential remediation funding. As they are forcing communities to host grid-scale projects, they should not leave those communities to shoulder the legal and other costs of cleanup.

Decommissioning tasks

The bulk of decommissioning work comprises dismantling and removing components: panels, racking, inverters, and cables, for example. In some cases, even landscaping is removed. Miles of wire must be removed from the ground unless buried beneath a certain depth. An exception: in a few cases, shallowly buried cables are left in place to avoid further environmental disruption, such as where they’ve been buried on wetlands.

In NYS, most racking is attached to driven or drilled steel piles; I haven’t seen concrete footings used for many utility-scale plants. Projects where ground penetrations have been avoided, such as landfills and over some geological features, may have concrete ballasts that must be removed.

Site restoration

The landowner usually specifies how the site will be used after decommissioning, and the decommissioning plan should state any known plans for the site.

Stockpiled topsoil is redistributed and the site is regraded as needed. Roads, concrete pads, and auxiliary structures are removed unless the owner wants to keep them. New substations or switchyards are often left in place and may be turned over to the utility company.

Agricultural soils will often require some decompaction (deep ripping). If drainage structures were removed or damaged during construction and operation, this is the time to replace them.

Developers like to claim that the solar hardware can be removed and farmland immediately tilled and planted; this seems unlikely, based on early studies.3 Hosting a solar plant is not the same as leaving land fallow. Most sites are—at best—managed minimally as turf, which can be result in uneven nutrient levels over a period of 30 or more years. The land is mowed regularly but not fertilized or otherwise amended. Expecting improvements in organic matter levels and overall soil quality is unrealistic, despite industry claims. Standard agricultural soil testing should take place and include zinc levels (from galvanized steel piles). Degradation in soil quality is particularly likely in areas shaded by panels.

Waste and salvage handling

ORES allows developers of grid-scale plants to claim a salvage/scrap value for items that may be sold for the materials they contain. Many municipalities do the same.

Most decommissioning plans state that solar panels and other components may be recycled, but the language is generally noncommittal. In cases where panels are taken to be recycled, often the “recycler” is a broker, not an actual facility. Sometimes only a few items are recycled, such as panel glass and aluminum frames. Of course, any parts of panels that are not recycled go into the waste stream.

Costs and funding

A decommissioning plan needs to state how much funding is expected, how estimates were established, how and when they will be updated, and what financial instrument(s) will be used. Considering the stakes and the timeframe, any security should be as free from risk as possible. Either cash escrow or cash bond is safer than a letter of credit. Decommissioning funds must be available regardless of current ownership and the owner’s solvency; they should also be independent of the bank’s credit rating and solvency. ORES generally accepts a letter of credit rather than cash escrow or bond. This option is too risky, in my view, for small municipalities with very limited resources.

Some local laws require a final estimate that is 25% higher than the basic estimate to help protect local communities; ORES only requires a 15% contingency premium. Once again, this favors the developer’s interests over community welfare. Solar projects tend to change hands regularly, so the decommissioning funding instrument must be transferable.

When preparing plans, municipalities have very little guidance on what costs to expect.4 NYSERDA’s sample numbers were taken from a 2-MW Massachusetts project with an unknown date, for instance, and the amounts stated are almost ludicrous in some cases. For example, they estimate $250 to seed what would probably be a 12-acre site. For an upstate NY project in 2023, seeding costs were estimated by the developer at $1,351 per acre, for a total of $16,212.5

Duration/schedule

The plan should make it clear how long decommissioning will take (typically 6-18 months, depending on the size and complexity of the facility). Certain work can only be performed at specific times of year, which may affect the time required for decommissioning.

Conclusions

Decommissioning planning is not a one-time process. Plans and costs must be revisited and updated on a regular basis; most decommissioning plans are to be reevaluated every five years and financial securities adjusted accordingly. Changes in salvage values, inflation, labor, tipping fees, and other costs must be tracked over a facility’s 30-60-year lifespan.

A report on decommissioning funding from the National Center for Energy Analytics observes:

Despite evidence that solar and wind facilities are deteriorating faster than previously claimed and despite significant costs for decommissioning, the majority of states have failed to protect consumers from the inevitable financial costs of decommissioning wind and solar facilities, in contrast to the rules imposed on oil and natural gas companies.6

The report assigns a letter grade to each state’s decommissioning policies for wind and solar facilities, from A to F, with only one state (Virginia) receiving an “A” grade. NYS received a “C.” By way of comparison, NYS received a “B” grade for oil and gas well decommissioning. Specifically, the report criticizes the letter of credit and other requirements from ORES:

The form of assurance could potentially not be secured, should financial circumstances change. The amount of assurance is too indefinite, and the timing of producing assurance is unclear.

NYS urgently needs a statewide requirement that all solar installations—both residential and utility-scale—must have decommissioning plans. Decommissioning funds must be provided for utility-scale projects of all sizes. ORES should respect the host community’s efforts to protect itself and not waive local laws that are more protective than the state requires. Given that communities are often selected in part because they are economically disadvantaged, they deserve all the protection the state can give them.

I hope you found this post useful. If you think it might help others, please click “like” to boost its position in Substack searches and to support my work.

Want to share this as a PDF? Here’s the file:

Photo credits: First three photos by Oregon Sensible Solar, which states on its website:

“Just outside Bonanza, OR, sits an eight-year-old solar farm, a stark testament to corporate neglect. Frames tilt haphazardly, cracked and shattered panels litter the overgrown fields, and frayed wires snake through desiccated weeds. The once-promising grid now resembles a derelict industrial site, a breeding ground for fire hazards with its accumulated dry vegetation and exposed electrical components. This decaying landscape underscores a disturbing reality: for some solar companies, profitability trumps responsible land stewardship, leaving our community to contend with the hazardous aftermath of their abandoned promises.”

Last photo shows racking collapsed on a Schenectady County, NY site; conditions remained in effect for 11 months.

Alfred Oaks Solar ($4.4 million), Bear Ridge Solar ($5.3 million), and Fort Edward Solar ($5.6 million).

A project in Rockland County (est. .5 MW) was removed shortly after being installed, but it did not go through a conventional decommissioning process as it had never been placed in service.

Maria Cristina Moscatelli, Rosita Marabottini, Luisa Massaccesi, Sara Marinari, Soil properties changes after seven years of ground mounted photovoltaic panels in Central Italy coastal area, Geoderma Regional, Volume 29, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geodrs.2022.e00500. The study showed a marked “striping” effect with rows of degraded soil under the panels separated by “normal” rows between them. This would need to be addressed during decommissioning.

Guidance, such as it is, is included in NYSERDA’s NYS Solar Guidebook, https://www.nyserda.ny.gov/All-Programs/Clean-Energy-Siting-Resources/Solar-Guidebook.

Alfred Oaks Solar Project, Town of Alfred, Allegany County, Site Restoration and Decommissioning Plan, 29 March 2023, https://documents.dps.ny.gov/public/Common/ViewDoc.aspx?DocRefId=e029de8b-0000-c658-86f1-671ec5f30b28.

National Center for Energy Analytics, A State-by-State Assessment of Financial Assurances Required for Decommissioning Wind and Solar Facilities, October 2025, https://energyanalytics.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/State-Financial-Assurance-Requirements-FINAL_10.7.25.pdf.

https://www.missilicon.com/process

Missippi silicon manufacturing process. LOL if one thinks we will ever get the energy back from production of silicon (solar panels). 99% of of panels are sourced from China who are by far the largest consumer of fossil fuels on our planet. Virtue signaling all the way to trillions in debt?

This article comes at the perfect time, thank you for brilliantly illuminating this critical, often-overlooked aspect of renewable energy infrastructure.